Posted by Nick Hunt

https://dark-mountain.net/to-the-bone/

https://dark-mountain.net/?p=37883

You can listen to an audio version of this story here

We didn’t stop clubbing the afanc with our paddles until we were sure its back was broken. On this point Reverend Williams had been most specific. ‘Don’t stop clubbing the afanc, boys, until you are sure its back is broken,’ he’d said. ‘Merely battering the bugger will not suffice. You must cleave its spine.’

He was sitting on a pony at the top of the first slope, where the track wound up into the mountain. He was wearing a black hat stiff with frost; his spectacles were steamed. His left hand held a small black book, in which his right hand diligently recorded which men were on their way up to the lake, and which men were on their way down.

We quickly climbed the rocky slope that ran up to the first great peak, beyond which the black lake lay. The land below was black and white, with no smudge of colour in between. The rock of the mountain stuck here and there through the drifted snow in a way that resembled porpoises breaking through a wave.

‘Don’t forget the head!’ the reverend called, his voice unsteady in the wind. Already we were high enough above him to make him appear just a black spot in the snow.

There were eleven men from my village altogether. We had played together as children. The anticipation made us children again, tripping each other on the narrow track, flinging echoes off the mountain walls. We teased fat Rhys, who had a face like a trout, that he might be mistaken for the afanc himself and get clubbed in its place. Our spirits were high with the reverend’s whisky and the sense of being part of something bigger than ourselves.

But it was a tricky climb to the lake, and soon enough the quietness overtook us. Before we were halfway to the top a light snow began to fall. We started to ache in our fingers and thumbs. The cold made us shrink inside our bodies, turned us to men once again.

Word of the afanc’s capture had spread far and wide. It had reached our village the previous night, and everyone knew that Reverend Williams of Beddgelert was requesting the help of every able-bodied man in the land. Bells had clanged between villages; summonses had gone out. They had even lit the old beacon on the cliff-top at Aberdaren, and now men from as far away as Ynys Enlli had come to lend a hand in the clubbing.

I’d have liked to have been there when the afanc was caught. I think I’d have preferred the beginning to the end. It must have been a powerful sight to see it bellowing on the shore, water spurting from its nose, lashing out with its tail. Chains had been fastened around its body, attached to teams of oxen. It was said that these oxen strained so hard in dragging the afanc from the lake that one of them popped an eye. It was also said that a chain had snapped, the creature had lurched and maliciously rolled over, and a father and son had had the lives crushed out of them.

I’d also have liked to have seen the maiden: the beautiful virgin they’d stationed there to lure the afanc to shore. If I closed my eyes I could picture her, all alone at the water’s edge. Her eyes nervously watching the lake, pretty face flushed with cold. Icicles sparkling in her hair, frost on her perfect lips. It was said that the beast couldn’t help itself: it had dragged its body from the murky depths, and laid its hideous head in the maiden’s lap.

It was also said that the maiden had offered to kiss the man who finished it off, the one who delivered that last blow. This was in all of our minds as we climbed; even fat Rhys, with the face like a trout. We gripped the wooden paddles the reverend had provided, swung them to feel their weight. The paddles felt serious and smooth in our hands. Anything was possible that morning.

We gripped the wooden paddles the reverend had provided, swung them to feel their weight. The paddles felt serious and smooth in our hands. Anything was possible that morning.

Ascending the final uphill stretch, we came upon a party of fifteen men coming in the opposite direction. They had purple faces and small, resentful eyes, squinting like sulky children. They appeared exhausted from their work; their hands were clawed with cold. They demanded cigarettes, which we gave. Few of them looked at us directly.

‘Have you come from the lake?’ asked Aled excitedly. None of them spoke, but one man nodded.

‘And how does it go?’ Aled asked again.

‘A hard job,’ said this man.

‘But it’s not finished yet?’

‘It’s not finished yet.’

‘And what’s the creature doing? Fighting back?’

‘Taking it,’ the man replied. There was a pause in which no one else spoke. And then they spat their cigarette butts into the snow and resumed their path down the mountain.

We heard the noise before we saw. At first we didn’t know what it was. Echoing from somewhere over the rise – beyond which, we knew, the black lake lay in the shadow of the peak – a steady whap-whap, whap-whap, whap-whap that sounded like slush dripping off a roof, or an audience clapping along to music.

‘That must be the sound of the beast’s great tail, slapping on the water,’ I heard Aled say. But it wasn’t, as we soon found out. It was the sound of the paddles.

There must have been twenty or thirty men actively clubbing away down there, with many more gathered round, awaiting their turn. The afanc lay in the middle of them all, tethered to the rock by chains. The paddles were going up and down, rebounding off the afanc’s flesh, rising and falling mechanically and without passion. The oxen huddled off to one side, dolefully swinging their horns.

The way I heard it related later, the afanc was the length of a barn and as high as an elephant. This wasn’t quite true, but it was still big; longer than a cottage or small orchard. At first it looked like an enormous seal, but then we saw the fur around the chops, the sullen, doggy features. It had a fish’s tail and fins, while its front appendages appeared to be something between paws and flippers. Its wrinkled muzzle was fastened with rope, and a few blunt teeth protruded. We got up close to look into its eyes; they were open, with an oily sheen. There was no expression in them.

We also passed the two bodies nearby: the father and son who’d been crushed when they first hauled it out. The bodies were laid on wooden boards with their feet pointing towards the lake and their heads towards the mountain. I could see the father’s likeness in the smooth face of the boy, and already a little snow had settled on it.

‘Where are you boys from?’ A short, stubbled man with a brown bowler hat had approached us.

‘Near Llanystumdwy,’ I told him. He noted this down, and the number in our group, in a small black book like the one the reverend had been keeping.

‘You see what to do. It’s not dead. We’ve been keeping this up since yesterday evening. We take it in shifts, two dozen at a time. Some of these boys could do with a rest. Go ahead.’

So we hefted our paddles and set to work. The clubbers wordlessly shifted aside to let us into the circle. I glanced at Aled, Ellis and Rhys and then raised my paddle high in the air, bringing it down hard on the gleaming flank. It bounced straight back, almost leaping out of my hand.

‘You got to watch for the bounce,’ said the man next to me without breaking his rhythm. ‘One fellow smashed his nose.’ Whap-whap, whap-whap, whap-whap, whap-whap. He let out a hiss with each impact, like steam escaping from a kettle.

I got the hang of his technique, following his swings. It was easy enough to fall into the rhythm, to learn which part of the handle to grip, how high to raise the paddle before bringing it down.

At first I found it enjoyable. It was like slapping a jelly. The afanc’s body was thick blubber, like the whale I saw once washed up on Black Rock Sands. The paddles rebounded off the rubbery hide, sending wobbles up my arms and into my shoulders. The regular smacks made the monster’s flesh shimmer like the skin of rice pudding.

‘Where’s the maiden?’ I asked the man beside me, glancing at the crowd. They were watching dully, mostly standing, eating scones and drinking beer. Not a beautiful virgin in sight. All I could see was men.

‘The maiden went home some time ago,’ the man beside me replied. He swung and hissed, swung and hissed. ‘She didn’t want to see.’

And so we settled into it. First the men on the left side swung, then the men on the right. Whap-whap, whap-whap, whap-whap, whap-whap. The rhythm helped us keep it together. I learned to anticipate the bounce, letting the paddle rise and fall like a pendulum, following its own momentum. The snow fell faster, then slackened off. Shadows moved across the lake. The wet slaps echoed off jagged rock walls that had been hacked for slate a hundred years before.

I was disappointed about the maiden, but focused on the job at hand. I was determined to keep pace with the others, to ensure my blows landed clean and hard, that my movements were as regular as a machine. I had never taken part before in a great work such as this. I was proud to be there with the boys from my village, with Aled, Ellis, Owain, Dai – even fat Rhys, with the face like a trout – the best men I had ever known.

We clubbed steadily for an hour and then took a break to rest our arms. My muscles ached initially, but little by little the ache burned away to leave a pleasant warmth, a numbness. The feeling was like after chopping up logs for a fire. We had each brought a bag packed by our mam, with bread, ham and apples. I shared my food with a couple of men who were standing a little way back from the lake, at a spot where we could see right down the mountain to the fields and even – if it had been a clear day – to the sea.

‘Reverend Williams thinks the afanc came from there,’ I said to the man beside me. ‘It got stranded up here when the waters went down. That was thousands of years ago, he says.’

‘Well it shouldn’t be here now.’ The man took another slice of ham, folded it into his mouth.

We returned to work, and clubbed all the way through the morning and early afternoon. The steady whap-whap, whap-whap went on. The afanc’s thick flesh began to soften and bruise. The paddles gave us splinters. I saw that the ground around our feet was covered in a layer of tiny black spines that must have once bristled from the hide; now all these spines had been snapped off, and the body was as smooth as a slug’s.

The next time I took my rest, I walked around to the front of the afanc to examine its quivering face. I could see no change in its expression. Its eyes were spotted with oily blotches; it was hard to tell if it could still see. I held the palm of my hand near one nostril but could feel no breath. Fur hung off its muzzle like wet moss, half torn away. A rope of saliva, or slime of some kind, attached its bottom lip to the ground.

‘Keep it up, boys,’ called the stubbled man in the bowler hat through a cloud of pipe smoke. ‘Eventually we’ll soften the muscle, loosen it down to the bone.’ He was still standing with his black book, though new arrivals were fewer now. There were still about forty men gathered round; always twenty active paddles.

‘We must break that back by nightfall, boys,’ he shouted again a little later, when the sun was lower in the sky. The afanc’s skin had turned a different colour, become blotched and darkened. My arms were swinging mindlessly, pounding a soft, shining dent in the flank. The motion had become so familiar to me that it felt strange when I stopped.

We kept it up through the long afternoon and into the first shades of evening. The land grew dim; shadows gathered and spread from the folds of the mountain. Snow began to fall again. Despite the warmth of exercise, we had to pull on extra layers, scarves and thick woollen jumpers that had been donated from the villages. The bitter wind whistled through the holes anyway. There weren’t enough gloves to go around.

Sometimes the rhythm of the paddles would change. I could almost close my eyes. It went from whap-whap, whap-whap, whap-whap into triples like a steam train picking up speed: whap-whap-whap, whap-whap-whap, whap-whap-whap, whap-whap-whap and then whappity-whappity-whappity-whappity until we lost the rhythm entirely and the sound became a cacophony, like applause. Sometimes it seemed I heard the impact before my paddle actually struck – the way soldiers say it is when you get hit by a bullet – and sometimes it seemed the sound was delayed, an echo in a well. But it didn’t matter whose impacts were whose, whose swings connected with which blows. We were working as one paddle now, a machine that didn’t know how to stop. I couldn’t feel my arms anymore. My hands felt a long way from my body, moving up and own of their own accord. They barely corresponded with any other part of me.

We were working as one paddle now, a machine that didn’t know how to stop.

I could feel by the way the paddle connected that the pounded blubber in front of me had changed in consistency; I was making headway now. All the bounce had gone out of the flesh, its tightness had been broken. The paddle no longer jumped back when it hit, but splatted wetly into soft mush, even sinking in a little. The light brown pulp reminded me of rotten pears; of the orchard at home, last summer’s pear jam. I had spoilt the skin and was breaking through fat, smashing the muscle to slop. I wanted to work further changes, batter and batter and batter this flesh until it became something else. There was bone down there. I could feel it knocking. My efforts redoubled, the paddle swung faster, pain stabbed into my shoulders and neck but somehow didn’t reach my brain; everything seemed far away. The snowflakes spiralled so fast they made me dizzy.

It took me some time to realise that someone was trying to get my attention, and more for my paddle to slow down enough to stop. A voice was addressing me from behind; a hand was on my shoulder. I glanced round from the mess of pulp to see my friends Owain, Ellis, Rhys and Dai, their features as screwed and purple-looking as the men we’d met descending the mountain all those hours before. Rhys had his trout face turned to the ground, and one of his arms was in a sling.

‘Dafydd, stop, just stop a second. Dafydd. Dafydd. Hold.’

‘Rhys can’t use his hand anymore. He can’t carry on. We’re going back.’

Rhys lifted his right hand apologetically, supporting it with his left. It was swollen from the wrist to the thumb, luridly purple and shining. His arm was trembling.

‘I can’t move my fingers,’ he mumbled at me, staring at his feet. There were tears welling in his small eyes. He moaned a little, and I couldn’t help thinking that if the beautiful maiden was here she’d have probably never have laid eyes on a man who looked quite so pathetic.

‘We’re going back, Dafydd. Are you coming or staying?’

‘I’m down to the bone,’ I said. ‘I can feel it. We can finish it now.’

‘We’re going back. There’s been enough of this.’

‘We’re there, we’re almost at the end.’

‘No, Dafydd. There’s been enough.’

‘All of you are going back?’ I asked, feeling the anger in me.

‘Aled says he’ll stay, if you won’t come.’

I looked at my own hands, torn and blistered, rubbed raw in patches. There were splinters worked under the skin that I wouldn’t get rid of for weeks. My hands were crabbed in the shape of the handle; it hurt when I straightened my fingers.

‘I’ll stay,’ I said. ‘I’m not leaving now.’

‘As you like. You keep going.’

They left their paddles in the growing pile beside the two dead bodies. I watched them retreating down the track, growing smaller in the darkness. Fat Rhys shambled in the middle with Owain’s hand on his arm. I waited until they were out of sight, motioned Aled to step up beside me, and fell back into rhythm.

There were only half a dozen of us left. Darkness moved up the mountain, seeping into the blackness of the lake. Before the night fully fell and the land around us was swallowed completely, the man in the brown bowler hat organised the lighting of torches, which encircled the afanc to cast shadows across its ruined body. The flames lit the snowflakes from beneath and turned them into nests of sparks. The faces of the remaining men looked like flickering masks. The wide world shrunk to this bubble of light, outside which nothing else mattered.

I concentrated on the bone. After these hours of working soft flesh it felt good to connect with a solid thing, though the impacts jarred my arms. My elbows and wrists absorbed the shocks. The blood in my veins seemed to ache. The sounds of the neighbouring paddles told me that others had also hit bone; they had changed to a hollow thock-thock, thock-thock, like axes against a tree. The clubbers were huffing with exertion now, urging each other on. We could feel that we were near the end, and all of us wanted to be the one there first.

‘This is the buried treasure, boys! This is what we’ve been digging for!’ The man in the brown bowler hat was holding his paddle like a flag. He had hopped up on the afanc’s back, slipping around in the skinless mush, thudding time with the heel of his boot.

‘Here’s the last nut to crack! Come on, come on!’ he shouted later when the beat was a frenzy, thock-thock, thock-thock, thock-thock, thock-thock, like one of those drums the Irish use, and the afanc’s body was bouncing from the blows. But we had stopped listening to him long ago. Our ears were tuned for one sound, one sound only.

And then it came: the unmistakable craaack. We felt it in our bones as well. And at once the paddles stopped.

It was Aled who’d swung the breaking blow. He had been working next to me. His paddle had stuck right there in the spine, wedged between two vertebrae. One by one, we went over to look. The vertebrae were as big as fists. The paddle had been jammed so hard he had trouble pulling it out.

While Aled tugged back and forth, trying to get his paddle back, I walked round to see the afanc’s face. It looked bloated in the light of the flames; its eyes were the texture of poached eggs. I bent close to its muzzle and heard a noise like escaping air, a bubbling moan that continued as Aled grunted and shoved at the spine, and then the body shivered and was silent.

‘That’s it, boys,’ concluded the man in the brown bowler hat in the quietness that came next. ‘The job is done. Like the reverend said.’

Later, I knew I would be disappointed. I knew I would feel it so keenly that I’d clench my fists and bite my tongue and still it wouldn’t help. I had been so close, it had nearly been me; perhaps just a few more blows. But Aled, Aled had got there first. Even without the maiden here, offering herself to him, my stomach would turn with resentment. My oldest friend. Back in the village I’d have to endure him relating this story again and again, while women crowded around, admiring him. It would make me tug the hair from my scalp. The afanc was wasted now.

But I didn’t feel that yet. I didn’t feel a thing. A wall of exhaustion hemmed me in. We stood quietly. Aled sighed. One man coughed, wiped his hands on his trousers. Another let fall his paddle. The man in the brown bowler hat looked as if he were about to speak again, but then he turned away to fill his pipe.

Some remained standing, some sat down. The only thing to sit on was the afanc. The tenderised flesh sunk downwards with my weight. I wedged my feet at an angle with the ground and leaned back with my arms folded across my chest, allowing my eyes to close. There was pain in my forearms, my wrists, my neck, but it was so distant I felt it might belong to someone else. The fat supported the back of my head like the cushions in a chapel support the knees. It sounded strange to hear no blows, like when a clock has stopped.

It was warm and it was numb at the same time. Snowflakes settled on my face and didn’t melt, and I thought of the two bodies lying on planks who cared even less than I did. It was the most comfortable bed I’d ever known. Like a mattress I imagined rich people slept on. One day, I thought, I would sleep on a mattress such as this.

I thought of the beautiful maiden beside me, how her arms would feel. I imagined taking her cold hand in mine, our fingers sticky with the afanc’s mush. I wiped a fleck of gore from her hair. My muscles hurt because she’d fallen asleep and was lying on my body. Our skin was stuck together in certain places.

And then, beneath our backs, the mattress moved. All of us felt it: it passed the length of the afanc’s body from head to tail. The slow bulging-out of something deep inside, like a trapped air bubble or a thought. As undeniable as that crack. Like something trying to shift itself from one place to another.

None of us spoke. None cursed or even sighed. But one by one we got back to our feet, kicked the snow from our boots, stretched our arms, picked up our paddles where we’d let them drop – and continued clubbing.

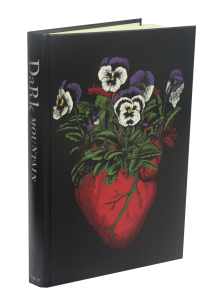

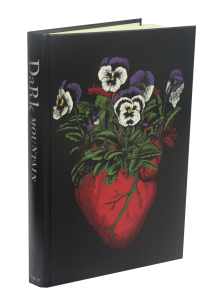

IMAGE: Earth Rites by Stuart Turner

Bone, horn, charred wood, beeswax

[Photo: Mim Saxl Photography]

This object is from a body of work inspired by a kayak trip around the lakes and islands of Finland. The experience of peaceful co-existence in a landscape that is still curious and unafraid of human encounters was both life-affirming and painful, coming as I do from a place where the life in the land is more hidden. I see the work as a bridge to an active relationship with the sacredness of place, story and rituals: domestic objects that are imbued with the memory of the materials used. Bowls become spirit boats, spoons become tillers to steer, ladles become mirrors to glimpse an ancestor; they wait for a lost tribe who may yet return.

Stuart Turner is a sculptor, outdoor educator, hedgelayer, coppice worker, carpenter and gardener. As an animist, he believes the soul gives shape to form and his work addresses those moments of connection that speak to a way of feeling and instinct beyond words, plans or outcomes. His creativity and inquiry has been shaped around issues of disconnection and reconnection with natural environments for many years.

Dark Mountain: Issue 27

Our spring 2025 issue is a hardback collection revolving around bodies, human and creaturely, plant and mineral, in an era of planetary breakdown.

Read more

The post To the Bone appeared first on Dark Mountain.

https://dark-mountain.net/to-the-bone/

https://dark-mountain.net/?p=37883